An Outing in War-Time

An Outing in War-Time is an article written by Arthur Conan Doyle published in The Strand Magazine in october 1915, and in Collier's on 2 october 1915 as Merry England in War Time.

Editions

- in The Strand Magazine (october 1915 [UK]) 1 photo, 7 illustrations by Alfred Leete

- in Collier's (2 october 1915 [US]) as Merry England in War Time, 3 ill. by Herbert Paus

Illustrations

- Illustrations by Herbert Paus in Collier's

-

-

-

- Illustrations by Alfred Leete in The Strand Magazine (october 1915)

-

An Outing in War-Time by A. Conan Doyle.

-

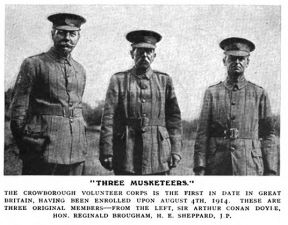

"Three Musketeers." The Crowborough Volunteer Corps is the first in date in Great Britain, having been enrolled upon august 4th. 1914. These are three original members - from the left, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Hon. Reginald Brougham, H. E. Sheppard, J. P.

-

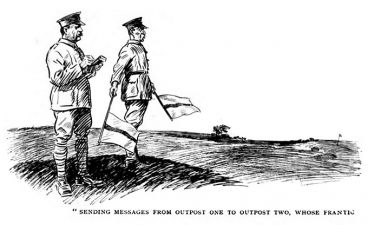

Sending messages from outpost one to outpost two, whose frantic...

-

... little flags are wagging away at the far end of the golf course.

-

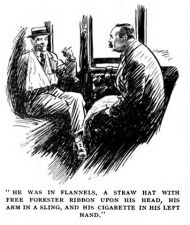

"He was in Flannels, a straw hat with free forester ribbon upon his head, his arm in a sling, and his cigarette in his left hand."

-

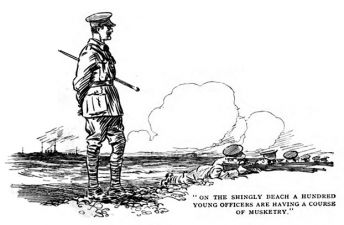

"On the shingly beach a hundred young officers are having a course of musketry."

-

"Four great biplanes are swinging and swooping above."

-

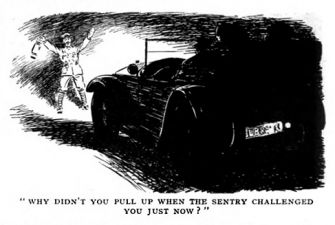

"Why didn't you pull up when the sentry challenged you just now ?"

An Outing in War-Time

I can well imagine that the day will come when our descendants will read with interest some details of how the War in this summer of 1915 affected the quiet country life of southern England that life of immemorial placidity where time passes so sedately to the gentle murmur of the breeze among the grasses and the bees upon the clover. It is a life so mellow and so gently peaceful that it might well have seemed in this island home to be beyond any caprice of Fate. And yet here we are stirred to our depths, every rule of conduct altered, every object of desire changed, with fiercer joys and sharper pains, and all our hearts in Flanders. It is good, no doubt, and it is very strange, though it has come upon us so gradually in these last eleven months that perhaps we hardly appreciate how topsy-turvy it has all become. One day set faithfully on record may serve as a type in years to come.

Children must have a change once in a while, war or no war, and the heat has made the little faces white and weary of late. Whither shall we take them ? Someone had mentioned Hayling Island. It is a hundred miles away, but my wife and I will be better for a complete break of thought. Too long have we been waiting for that which never comes, living during the night for the morning papers, living during the day for the evening one. It is a morbid state. One long day we shall have in the open to Hayling and back in search of rooms. The motor is ordered for twelve.

I am down at eight and walk among the flowers before breakfast. Hark to that sound breaking in upon the peace of this sweet summer morning ! It is very faint and very far, and yet with a deep throb in it which tells of infinite power. There it is again, rising a little and then falling, like a thunderous surge upon a distant beach. There is no doubt at all about the sound. It is that of the guns in Flanders. It is a hundred and twenty miles as the crow flies, and it might well have appeared incredible, but you have also to remember that we are seven hundred feet high and that there is a very steady easterly wind. Some miracle has put those air-currents just right, and we do actually hear the guns of the great long-drawn battle. For a week now, ever since the wind has been in that quarter, we have heard it. All this section of Sussex is talking of it. It brings it all very close, and when we volunteers muster of an evening for our drill, it helps to give actuality to the eternal " Upon the left form line of platoons !" or " Wheel to the right by sections !" when we hear the far-off roar of the whirlpool which has drawn in so much, and may yet draw in ourselves if we should be thought worthy. One can spring to attention with a sharper snap when the guns of Flanders are pulsing in one's ears.

Everybody is smiling this morning over a story that a Zeppelin was seen during the night near Tunbridge Wells. It is unlikely, but they all seem to believe it. These Zeppelin yarns have been a great boon to the country, bringing a little harmless excitement into the Sleepy Hollows. Here and there, no doubt, the machines have done a little damage, but if you put it all together it would not amount to that which is caused by a single large accident in peace time. Half-a-dozen able-bodied Suffragettes would cause more damage to property than all the Zeppelins that have ever come out of Germany. When one considers, on the other hand, that several of them have been destroyed, and that in one case — that of Warneford — twenty-eight of the crew were dashed to pieces, it seems to me that Germany's air fleet has up to date made as bad a bargain as her water fleet did when it killed two hundred civilians in Hartlepool,. Scarborough, and Whitby, but lost the Blucher with eight hundred men in endeavouring to repeat the glorious exploit. It is wiser as well as better to play the game.

Another story has just come in at which no one will smile. One of our aviators has fallen at Cross-in-Hand, five miles to the south. The accident, whatever it may have been, occurred high above the clouds. He fell like a stone for two thousand feet or more. What a terrible, and yet, on second thoughts, what an enviable end ! One can picture it — the sudden snap which showed that something had broken, the peremptory death call coming so quickly that the soul had hardly time for one flutter of apprehension. Then the long, swift. downward swoop with a gale roaring upwards past one's falling body — and then painless oblivion. So merciful is Nature that when one has survived a similar experience, not only is there no memory of pain, but even the events which led immediately up to it have been erased from the mind lest some brooding horror should survive. A huge switchback swoop ending in euthanasia. It is only terrible to the bystander who gathers the shattered frame. The man himself knows nothing.

Breakfast is over, and here comes the first task of the day — a curious example of topsy-turvydom, yet now accepted as a matter of course. For an hour and a half we are doing semaphore and Morse upon the common. Could there a year ago have been in this world a less likely thing than that I, a middle-aged civilian with no knowledge of such work, should be spending my morning with a magistrate, an architect, and another in sending messages from Outpost One to Outpost Two, whose frantic little flags are wagging away at the far end of the golf course ? Collectively, we are the signal section of the local company. Our peace of mind is blighted by the trick of one of our distant senders, who will drop his semaphore flag on the A and the G until it is blended with the other flag which he holds between his legs. We flap reproaches at him, but he is incorrigible. Still, it is all good work, and every lesson counts. At twelve I am hack at home, and the motor speeds upon its way.

In this little Sussex village we have ten thousand men — the 1st Lancashire Reserve Division of Territorials. Their khaki figures are everywhere — smallish men, as one would expect from the great manufacturing cities — but sharp and tough. They are Manchester for the most part, and they talk with a burr like a motor-cycle. What a change this glorious countryside must be to them, and what visions of the heather-clad south they will bear back to the dark streets of the busy north ! All their lives these days will come back to them in their dreams. Their comrades are in the Dardanelles, and they send constant drafts to them. Many a Manchester lad has already laid down his life between Krithia and the sea in the desperate venture of the last crusade.

Great Britain is one huge barracks, or like an Imperial military exhibition with samples strewn over the country. The oddest people are found in the oddest places. I remember at Edinburgh Castle seeing a hard-bitten regiment drilling admirably with "N.D." upon their shoulder-straps. I was unable to fit them into any conceivable type of Northumberland men. They proved on inquiry to be Newfoundlanders, fishers off the codbanks many of them, who had taken up their rifles for the common cause. So here in the little village of Maresfield, just four miles on our way, one is aware of long, slab-sided fellows with Stetson hats, which give their nationality. They are Colonel Panet's Canadian Horse Artillery, eating their hearts out because the cavalry have gone and they have been held back. All the charms of the dear old rose-embowered village, with its Norman church and famous Shelley manor-house, are as nothing to these fellows in their longing for the trenches of Flanders. Beside them are three regiments of English yeomanry of the Home Counties — all eagerly waiting, Uckfield, the next village, is full of sunburned infantry, and so is Lewes. Outside the ancient gate of the Norman castle there are swarms of them, and one can see them exercising on the long slope of the down where, just six hundred and fifty years ago, Simon de Mont fort drove the King's army headlong down into the town, and gave young Edward his first bitter taste of war. One notes as one passes that outside the police-stations are hung placards with types of aeroplanes upon them, that one may distinguish friend from foe. One would think that by their deeds one might know them.

We break away before we enter Brighton and take the back road, which proves to have every possible disadvantage — bad going, and most uninteresting and hideous. The monotony of the journey is broken only by a long wooden bridge which assures us, upon a placard, that, while we have to pay sixpence to pass over, the authorities will not guarantee, or hold themselves responsible for, our safe arrival upon the other side. On the right is Lancing School, perched upon its height. The sight of it saddens us, for it reminds us of a brave lad fresh from it wounded in his first battle and killed in his second over yonder in Flanders, What have the public schools not done for Britain in this war ! We had vamped up a great army — an army which surely is one of the wonders of the world, for every man is a pure volunteer without even the temptation of a bounty, and yet the total is greater than that of the armies of North and South together in the great American War. But one thing was vital and apparently impossible. Where were we to get the officers for millions of men ?

An officer is born, not made. In Prussia they had them in their thousands by hereditary caste, Where could we find them in our democratic country ? And then in an instant they appeared, this endless stream of dear j eager boys from the public schools, trained to unquestioning obedience upon the one side and to enforcing discipline upon the other* They came in hundreds and in thousands, these glorious lads, filling the gaps in the regulars and furnishing the subalterns for the new formations. "There never was such a grand chance for the public schools," wrote one of them, now lying buried in his trench at Ypres. In some schools I am told that more than eighty per cent, of those available went to the Front, They saved England , for they supplied what she sorely needed, and could have found in no other way. The men loved therm "They would have followed them, singing, into hell." I will always carry in my remembrance a chance meeting and chat in a railway-carriage with one of these boys — a boy with the hard, quick eyes of a man. He was in flannels, a straw hat with Free Forester ribbon upon his head; his arm in a sling, his cigarette in his left hand, his brown, earnest face thrust forward, and his talk of sandbags and saps, and above all of the splendour of his men. How often in the last twenty years have I contended that Britain is neither degenerate nor weakening, and that her history lies in the future rather than in the past! These youngsters will carry on the best that the race can give.

We have our lunch at Broadwater in one of those unpretentious English hostelries which are often so much better than they look. Then on through Arundel, with the glorious modern castle upon the right, and past Chichester, Emsworth, and Havant, until we reach Hay ling about four o'clock in the afternoon. The war still pursues us. On the shingly beach a hundred young officers are having a course of musketry. The place resounds with words of command and the snapping of triggers. Out to sea we can see upon the right the forts of Spithead, and in front of us a low, squat, sea-bully of a battleship, making her way eastwards, with a lean torpedo-boat gliding upon either quarter. It is a calm day, and we look anxiously over the smooth water for a periscope — the dorsal fin of the deadliest of sharks, I have seen, when I was in the Arc tic , a creature which lived upon sharks. Is it possible that these sharks also have such a master ? "Success of our submarines !" One sees the phrase in many of the ignorant German papers. May it, perhaps, be preserved as one of the grimmest and most sardonic jokes of history. Well, they were given the dirtiest task that ever fighting seamen undertook. If their own fate is sometimes hard, what about the North Sea fishermen whom they murdered in such cold blood with their shell-fire, Such deeds were never done in war before, On land and sea the Germans have always fought foul — it is sad that such a reproach will for ever rest upon a brave people.

Our business done, we are speeding back, taking the coast road this time. Submarines or no, one has only to glance seawards to be sure that our trade has not been seriously affected. This so-called blockade began on February 18th. It is now July 10th, and the Channel is still dotted with our merchant ships. There seem to me to be more than in peace time, but many of these are bound, no doubt, for Flanders. What risk and what expense would have been saved had we built our Channel tunnel in time ! It transcends the story of the Suez Canal as an example of our national slow-wittedness. It is lucky that we have other qualities that atone. But our descendants will pay good bard cash for many a long year to atone for this particular piece of absurdity.

Here is a great sight as we approach Brighton, There is an aerodrome by the sea, and four great biplanes are swinging and swooping above it. May they soon be above Essen ! There is the central ganglion of the whole German system. Paralyze that, and the huge fierce body lies inert. It is a long flight, no doubt — a good two hundred miles as I reckon it from the nearest friendly post — and yet surely it can be done. There are plenty of men who would go, even if they knew they would never come back. For it is the one operation of war which, if done on a sufficient scale, would indeed be final. Blast this infernal plague spot off the face of the earth I Perhaps even these biplanes may be units in that great fleet which may gather one day soon over the roaring furnaces and smoking chimneys of the great Westphalian death factory.

It is dark as we leave Brighton, for we have stopped there to dine, and as we start upon the twenty-five miles run which will bring us home we are warned that no lights of any kind are allowed along the front. This prohibition is in force in all the seaboard towns, and the object is supposed to be not only us a protection against possible Zeppelin raids ? but as a means of preventing hostile submarines out at sea from taking their bearings. We crawl along a pitch-black front, with the shadowy form of other cars gliding past us. Every window is darkened. Who could believe that this is the Parade which only a year ago was the brightest and gayest promenade in England ? It is good, for it brings the War home to the people, and as our folk have little imagination some tangible sign is needed. It impresses them more if it makes them uncomfortable, as the boys of old used to be whipped on the boundaries of the commons so that they would always carry them in their minds.

Once out of Brighton we switch on our lights, and are soon well upon our way. But light or dark, the War is always with us. As we pass the level crossing of the railway at Uckfield a policeman holds us up, vigorously swinging a lantern.

"Why didn't you pull up when the sentry challenged you just now ?"

"We heard no sentry."

"You might have been shot. He challenged and got no answer."

We expressed our regrets, and the big man faded away into the darkness., still shaking his head and his lantern in mute reproach.

Our next episode was a more extraordinary one. Again we were aware of a form in the middle of the road ; and of a waving of hands. We were also vaguely conscious of a second figure which formed a blur upon the footpath. This time it was a business-like corporal of Military Police who had stopped us.

"I have a drunk prisoner here, sir, and I have to get him to Maresfield. Will you help me to do so ?"

"Can you manage in the front sent ?"

"Yes, sir."

"All right ; come along."

It is some miles out of our way, but in war-time one must do what one can. The corporal heaves and strains, and a minute later he is sealed beside the chauffeur, his captive like a sawdust doll, lolling this way and that in fantastic angles as we fly upon our way. The rush of night air seems to rouse the rascal, and we hear vague remonstrance, with frantic pawing of hands, but the corporal is skilled at the game, and holds him in some weird jujitsu grip. I tremble for my wife's ears, and for my motor's wind-screen 7 as the fellow becomes more lively. However, here we are at the entrance of an old English park, once the home of Shelley, the poet, and the car has pulled up at an outlying building converted into a guard-room. At a call a dozen men have appeared, and the corporal marches off with his prisoner. An instant later he is back.

"What are your charges, sir?"

And then, sinking his voice and with the air of one who gives the straight tip, "Not out of pocket, sir, but charged to the brigade."

Evidently he thinks that the chance of my life has come. The corporal clearly puts me down as a simpleton when I assure him that there is no money in the transaction.

We turn the car, and speed on our way once more.

But even now our adventures of the night are not at an end. There is the glare of a great fire upon our right in the direction of Crowborough Camp, We are speculating as to its cause, when again we are held up by dark figures and dancing lanterns. An officer's patrol this time, wanting to know who we are, whence we come, and what we are doing. It seems that there has been an incendiary fire, that there is reason to put it down to spies, and that all motor-cars are under suspicion. Fortunately we are near home now, and our identity is easily proved. At eleven o'clock we reach our harbour once again.

But even now my war day is not ended. Our volunteers are holding a farmhouse with a line of sentries, and I have promised to try and break through. It is not too late, as they are on duty till midnight. There is just time to get a black cloak and rubber-soled shoes, and there follows an hour of the most interesting of games, skulking in the shadow of hedges, creeping down the darker side of walls, waiting breathlessly while the sentry's dark figure passes, and then hurrying swiftly on to make ground before he turns upon his beat. No need to recount the successive stages of my venture, save that last one which found me discovered and challenged when I was but a few yards from the very heart of the defences.

And so, long after midnight, to bed, The window of my bedroom is open, and as I take a last look out at the starry sky I hear fur off the same dull throbbing roar with which the day began. It is the guns of Flanders, calling, calling, with their terrible voices, to me, to you, to all of us, to be up and ready for what the future may send.

More sources

- Collier's (2 october 1915)

-

p. 5

-

p. 6

-

p. 35