Henry Irving

Sir Henry Irving (6 february 1838 - 13 october 1905), born John Henry Brodribb, sometimes known as J. H. Irving, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility (supervision of sets, lighting, direction, casting, as well as playing the leading roles) for season after season at the Lyceum Theatre, establishing himself and his company as representative of English classical theatre. In 1895 he became the first actor to be awarded a knighthood, indicating full acceptance into the higher circles of British society.

Between 1894-1905, he played Corporal Gregory Brewster in the play A Story of Waterloo, written by Arthur Conan Doyle adapted from his short story A Straggler of '15 (1891).

Theatre

- 1894-1905 : A Story of Waterloo (as Corporal Gregory Brewster)

Conan Doyle about Henry Irving

In his autobiography Memories and Adventures (1923), Arthur Conan Doyle wrote about Henry Irving :

« Henry Irving is one of the other great men whom I have met at close quarters, for his acting of Gregory Brewster brought us in contact. When he was producing "Coriolanus" he came down to Hindhead and used to drop in of an evening. He was fond of a glass of port—indeed, he was one of the four great men who were stated (probably untruly) by the Hon. G. Russell to drink a bottle each night—being the only trait which these great men had in common. The others, I remember, were Tennyson, Gladstone and Moses Montefiori, and the last I believe was really true. Like all bad habits, it overtook the sinner at last, and he was cut off at the age of 116.

Irving had a curious dry wit which was occasionally sardonic and ill-natured. I can well believe that his rehearsals were often the occasion for heart-burnings among the men and tears among the ladies. The unexpectedness of his remarks took one aback. I remember when my friend Hamilton sat up with me into the "wee sma' hours" with the famous man, he became rather didactic on the subject of the Deity or the Universe or some other tremendous topic, which he treated very solemnly, and at great length. Irving sat with his intense eyes riveted upon the speaker's face, which encouraged Hamilton to go on and on. When at last he had finished, Irving remarked: "What a low comedian you would have made!" He wound up his visit by giving me his copy of "Coriolanus" with all his notes and stage directions—a very precious relic.

Many visions of old times rise before my eyes as I write, but my book would lose all proportion should I dwell upon them. I see Henley, the formidable cripple, a red-bearded, loud-voiced buccaneer of a man who could only crawl, for his back appeared to be broken. He was a great poet and critic who seemed to belong to the roaring days of Marlowe of the mighty line and the pothouse fray. I see Haggard too, first as the young spruce diplomatist, later as the worn and bearded man with strange vague tendencies to mysticism. Shaw, too, I see with the pleasant silky voice and the biting phrase. It was strange that all the mild vegetables which formed his diet made him more pugnacious and, I must add, more uncharitable than the carnivorous man, so that I have known no literary man who was more ruthless to other people's feelings. And yet to meet him was always to like him. He could not resist a bitter jest or the perverted pleasure of taking up an unpopular attitude. As an example I remember Henry Irving telling me that when Shaw was invited to his father's funeral he wrote in reply: "If I were at Westminster Henry Irving would turn in his grave, just as Shakespeare would turn in his grave were Henry Irving at Stratford." I may not have it verbally exact, but that was near enough. It was the kind of outrageous thing that he would say. And yet one can forgive him all when one reads the glorious dialogue of some of his plays. He seems subhuman in emotion and superhuman in intellect.

Shaw was always a thorn in Irving's side, and was usually the one jarring note among the chorus of praise which greeted each fresh production. At a first night at the Lyceum—those wonderful first nights which have never been equalled—the lanky Irishman with his greenish face, his red beard, and his sardonic expression must have been like the death's-head at the banquet to Irving. Irving ascribed this animosity to Shaw's pique because his plays were not accepted, but in this I am sure that he did an injustice. It was simply that contrary twist in the man which makes him delight in opposing whatever anyone else approved. There is nothing constructive in him, and he is bound to be in perpetual opposition. No one for example was stronger for peace and for non-militarism than he, and I remember that when I took the chair at a meeting at Hindhead to back up the Tsar's peace proposals at The Hague, I thought to myself as I spied Shaw in a corner of the room: "Well, this time at any rate he must be in sympathy." But far from being so he sprang to his feet and put forward a number of ingenious reasons why these proposals for peace would be disastrous. Do what you could he was always against you. »

-

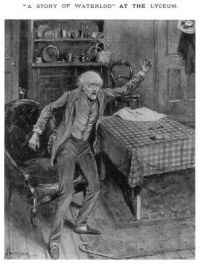

A scene from the play A Story of Waterloo with Mr. Irving as Corporal Gregory Brewster (left)

(Illustration by John Percival Gülich in The Graphic, 29 september 1894). -

A Story of Waterloo with Mr. Irving as Corporal Gregory Brewster (center)

(Illustration by Fritz Braundel in the South London Press, 18 september 1897).