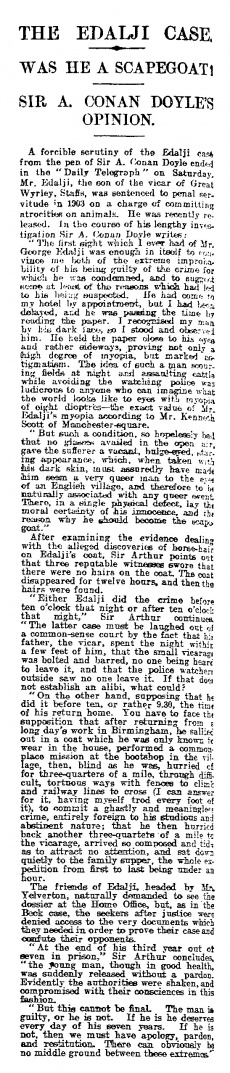

The Edalji Case. Was he a Scapegoat?

The Edalji Case. Was he a scapegoat? is an article published in the Daily Mail on 25 january 1912, including extracts of the article written by Arthur Conan Doyle (initially published in The Daily Telegraph on 11 & 12 january 1907).

The Edalji Case

Was He A Scapegoat?

A. Conan Doyle's Opinion.

A forcible scrutiny of the Edalji case from the pen of Sir A. Conan Doyle ended in the "Daily Telegraph" on Saturday, Mr. Edalji, the son of the vicar of Great Wyrley, Staffs was sentenced to penal servitude in 1903 on a charge of committing atrocities on animals. He was recently released. In the course of his lengthy investigation Sir A. Conan Doyle writes:

The first sight which I ever had of Mr. George Edalji was enough in itself to convince me both of the extreme improbability of his being guilty of the crime for which he was condemned, and to suggest some at least of the reasons which had led to his being suspected. He had come to my hotel by appointment, but I had been delayed, and he was passing the time by reading the paper. I recognized my man by his dark face, so I stood and observed him. He held the paper close to his eyes and rather sideways, proving not only a high degree of myopia, but marked astigmatism. The idea of such a man scouring fields at night and assaulting cattle while avoiding the police was ludicrous to any one who can imagine what the world looks like to eyes with myopia of eight dioptres — the exact value of Mr. Edalji's myopia, according to Mr. Kenneth Scott of Manchester-square.

"But such a condition, so hopelessly bad that no glasses availed in the open air gave the sufferer a vacant, bulge-eyed, staring appearance, which, when taken with his dark skin, must have made him seem a very queer man to the eyes of an English village, and therefore to be associated with any queer event. There, in a single physical defect, lay the moral certainty of his innocence, and the reason why he should become the scapegoat."

After examining the evidence dealing with the alleged discoveries of horse-hair on Edalji's coat, Sir Arthur points set that three reputable witnesses swore that there were no hairs on the coat. The mat disappeared for twelve hours, and then the hairs were found.

"Either Edalji did the crime before 10 o'clock that night or after 10 o'clock that night," Sir Arthur continues. "The latter case must be laughed out of a common-sense court by the fact that his father, the vicar, spent the night within a few feet of him, that the small vicarage was bolted and barred, no one being heard to leave it, and that the police watchers outside saw no one leave it. If that does not establish an alibi, what could?

"On the other hand, supposing that he did it before 10 or rather before 9:30, the time of his return home. You have to face the supposition that after returning from a long day's work in Birmingham. he sallied out in a coat which he was only known to wear in the house, performed a commonplace mission at the bootshop in the village, then, blind as he was, hurried off for three-quarters of a mile through difficult, tortuous ways, with fences to climb and railway lines to cross (I can answer for it, having myself trod every foot of it) to commit a ghastly and meaningless crime, entirely foreign to his studious and abstinent nature; that he then hurried back another three — quarters of a mile to the vicarage, arrived so composed and tidy as to attract no attention, and sat down quietly to the family supper, the whole expedition from the first to the last being under an hour.

"The friends of Edalji, headed by Mr. Yelverton, naturally demanded to see the dossier at the Home Office, but, as in the Beck case, the seekers after justice were denied access to the very documents which they needed in order to prove their case and confute their opponents.

"At the end of his third year out of seven in prison," Sir Arthur concludes, "the "axing man, though in good health, was suddenly released without a pardon. Evidently the authorities were shaken, and compromised with their consciences in this fashion.

"But this cannot be final. The man is guilty, or he is not. If he is he deserves every day of his seven years. If he is not, then we must have apology, pardon, and restitution. There can obviously he no middle ground between these extremes."