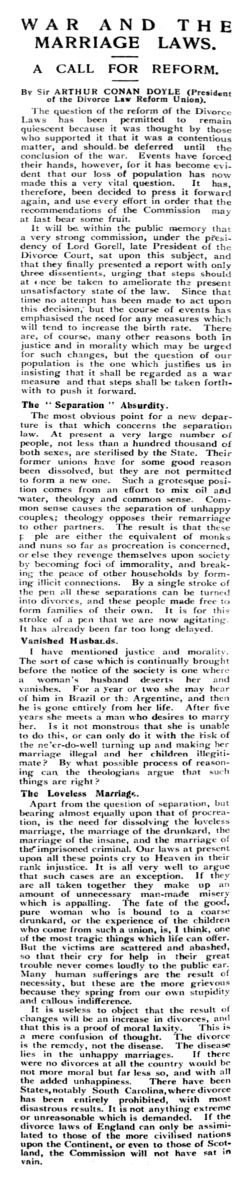

War and the Marriage Laws

War and the Marriage Laws is an article written by Arthur Conan Doyle published in the Evening Standard on 6 july 1917.

War and the Marriage Laws

A CALL FOR REFORM.

By Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (President of the Divorce Law Reform Union).

The question of the reform of the Divorce Laws has been permitted to remain quiescent because it was thought by those who supported it that it was a contentious matter, and should. be deferred until the conclusion of the war. Events have forced their hands, however, for it has become evident that our loss of population has now made this a very vital question. It has, therefore, been decided to press it forward again, and use every effort in order that the recommendations of the Commission may at last bear some fruit.

It will be, within the public memory that a very strong commission, under the presidency of Lord Gorell, late President of the Divorce Court, sat upon this subject, and that they finally presented a report with only three dissentients, urging that steps should at once be taken to ameliorate the present unsatisfactory state of the law. Since that time no attempt has been made to act upon this decision; but the course of events has emphasised the need for any measures which will tend to increase the birth rate. There are, of course, many other reasons_ both in justice and in morality which may be urged for such changes, but the question of our population is the one which justifies us in insisting that it shall be regarded as a war measure and that steps shall be taken forth-with to push it forward.

The "Separation" Absurdity.

The most obvious point for a new departure is that which concerns the separation law. At present a very large number of people, not less than a hundred thousand of both sexes, are sterilised by the State. Their former unions have for some good reason been dissolved, but they are not permitted to form a new one. Such a grotesque position comes from an effort to mix oil and water, theology and common sense. Com-mon sense causes the separation of unhappy couples; theology opposes their remarriage to other partners. The result is that these people are either the equivalent of monks and nuns so far as procreation is concerned, or else they revenge themselves upon society by becoming foci of immorality, and breaking the peace of other households by forming illicit connections. By a single stroke of the pen all these separations can be turned into divorces, and these people made free to form families of their own. It is for this stroke of a pen that we are now agitating. It has already been far too long delayed.

Vanished Husbands.

I have mentioned justice and morality. The sort of case which is continually brought before the notice of the society is one where a woman's husband deserts her and vanishes. For a year or two she may hear of him in Brazil or the Argentine, and then he is gone entirely from her life. After five years she meets a man who desires to marry her. Is it not monstrous that she is unable to do this, or can only do it with the risk of the ne'er-do-well turning up and making her marriage illegal and her children illegitimate? By what possible process of reasoning can the theologians argue that such things are right ?

The Loveless Marriage.

Apart from the question of separation, but hearing almost equally upon that of procreation, is the need for dissolving the loveless marriage, the marriage of the drunkard, the marriage of the insane, and the marriage of the imprisoned criminal. Our laws at present upon all these points cry to Heaven in their rank injustice. It is all very well to argue that such cases are an exception. If they are all taken together they make up an amount of unnecessary man-made misery which is appalling. The fate of the good. pure woman Who is bound to a coarse drunkard, or the experience of the children who come from such a union, is, I think, one of the most tragic things which life can offer. But the victims are scattered and abashed, so that their cry for help in their great trouble never comes loudly to the public car. Many human sufferings are the result of necessity, but these are the more grievous because they spring from our own stupidity and callous indifference.

It is useless to object that the result of changes will be an increase in divorces, and that this is a proof of moral laxity. This is a mere confusion of thought. The divorce is the remedy, not the disease. The disease lies in the unhappy marriages. If there were no divorces at all the country would be not more moral but far less so, and with all the added unhappiness. There have been States, notably South Carolina, where divorce has been entirely prohibited, with most disastrous results. It is not anything extreme or unreasonable which is demanded. If the divorce laws of England can only be assimilated to those of the more civilised nations upon the Continent, or even to those of Scots land, the Commission will not have sat in vain.